In case you were wondering, I have decidedly unexotic and Catholic heritage- generic Irish/English stock on my Dad’s side and on my Mum’s side, half Northern Italian and half more of the same. I am, as they say, an anglo mongrel, and the food I grew up on reflects that fact. I am sometimes accused, mostly jokingly but with a dash of truth thrown in, of growing up ‘without culture’ by my partner, his heritage being a mix of Portuguese and Iraqi Jew now considered exotic.

In a way, I think as Australians we shortchange ourselves when we say we have ‘no culture’. We have every culture, that’s the point, and we can serve it all up on a plate and pretend for five minutes that we are all friends. It solves nothing, but it feeds everyone. And there are things that I think all of us who love food understand. Many of the conversations we had growing up centred on food. What did you have for lunch, what should we have for dinner, have you eaten? These are universal questions for perpetually hungry and food-obsessed families, whatever their nationality.

Food for me is mostly all about my mother. It is the same for my partner, on the phone to his mum trying to suss out exactly the right methods or ingredients to get that thing she made for him as a kid just the way she made it. If we cook something our parents used to make, and try to make it the way they would when we were kids, it is kind of ritual, a kind of homage. Whether that thing be a sausage sanger or a perfectly rendered matzo ball, we can chow down on each with equal gusto.

This recipe is basically eggplant parma, a combination of a traditional eggplant fritter recipe from my Grandfather’s family and the tomato sauce that we would eat in some form at least once a week when I was growing up. I would happily subsist on slow-cooked tinned tomatoes for the rest of my life, and this is one mind-numbingly delicious way of serving it.

Eggplant Parmigiana

Serves 8 generously, if served with salads and sides.

2 enormous eggplants, cut into ½ centimetre slices

1 egg, lightly beaten

1 cup flour

1 stale baguette, blended in the food processor

olive oil, for shallow frying

Extra virgin olive oil

2 small onions, finely chopped

pinch chilli flakes

pinch salt

6-8 cloves garlic, finely chopped

4x 400g tins chopped tomatos

1/2 cup red wine

2 sprigs rosemary (optional)

500g mozzarella, sliced

150g good quality parmesan or romano cheese, grated

Tip: You can either make the sauce first or take the ‘do everything at once approach’ outlined below, just keep in mind that the sauce should cook for at least an hour. The whole dish can be made a few days in advance; once everything is layered together, refrigerate and when you want to serve it, bring it up to room temperature before cooking.

Salt the eggplant slices well, layer on a plate and place a heavy object on top. Arrange three bowls on the bench, 1 with the flour, 1 with the beaten egg, and 1 with the breadcrumbs. Leave the weighted eggplant slices to sit for 20 minutes.

Heat the oil in a large pan. Cook the onions until translucent, then add the salt, chilli flakes and garlic. Cook until all ingredients are done but not brown. Add the wine to deglaze the pan, cook a couple of minutes. Add the tomatoes, give the tomato tins a bit of a rinse and pour the resulting water in too. Simmer the sauce for 45 minutes – 11/2 hours, adding in the rosemary about halfway through.

While the sauce is simmering, rinse the eggplants and pat dry. Heat the oil in a large frying pan to shallow fry the eggplant. Then it is just a matter of dipping each eggplant slice in flour, then egg, the breadcrumbs and popping them into the oil. Turn each slice over so it browns on both sides, and when done, put the slices on a plate lined with paper towel to drain well. This process takes about the same amount of time as simmering the sauce.

Remove the rosemary from the sauce, give the mixture a quick blitz with a stick blender if too lumpy, and leave to cool.

Preheat the oven to 180 degrees C. In a large baking dish, layer the sauce, then the eggplant slices, then the mozzarella and then the parmesan romano until the dish is full or the ingredients are exhausted – whichever comes first. Bake for around 45 minutes or until the top is browned.

Do you have a favourite family recipe?

In my household, I do most of the cooking, because I’m speedy, pragmatic, and an absolute control freak. Everything I make is geared towards minimum effort for maximum results. As such I don’t prepare many of what I perceive to be ‘high risk’ foods.

So on Sunday when my boyfriend, Senhor R, offered to whip up a Pudim Flan (Crème Caramel) this week, I was all for it, even though neither of us have ever attempted to make such a thing. It turned out to be remarkably simple, which is in no way a reflection on his culinary skills. And it was so delicious that he actually made another one on Wednesday! I could get used to this…

Growing up, every Portuguese restaurant I ever went to had three staple deserts; Mousse Chocolate, Arroz Doce (Sweet Rice) and Pudim Flan (Crème Caramel), to be washed down with as many ‘bicas’ (espressos) as possible. Although there were occasional surprises such as Baba de Camelo (camel’s dribble) or the potentially explosive Molotov Pudding, you could always find these three.

My Mum had the monopoly on the Mousse Chocolate market and was not averse to making her own custard for other desserts, but she never attempted a Pudim Flan. It remained an elusive delicacy that other peoples’ mums brought to feast-like gatherings, or something made in restaurants by people who understood such things.

The closest we ever got to Pudim Flan was a packet of this dried stuff sitting in our pantry for many years. It’s possibly still hiding there somewhere. I have a dim memory of a packet being attempted once, but clearly with poor results as it was never spoken of again.

Then in Argentina Lau discovered her love for flan, mostly through her delight of dulce de leche which is always offered with it. The Flan was an excellent excuse to eat the giant dollop of dulce, much in the way few people actually add more than a token amount of milk to their Milo to legitimise the ‘drink’ status of it.

Last weekend as I was idly flipping through a Portuguese cookbook, and I came across this recipe and, armed with an abundance of fresh eggs I went to work. The question was – would Lau like it without the dulce de leche?

Pudim Flan from The Taste of Portugal by Edite Vieira

Caramel

110g sugar

3 Tablespoons of water

Custard

4 eggs

90g sugar

450ml milk

Preheat the oven to 180° C.

Pour the 100g sugar into the pan with the water and rapidly heat until all the mixture has ‘foamed’ and becomes a golden liquid caramel. Pour the caramel into the bottom of a round dish- I used a 7 cup pyrex storage dish. Turn the dish quickly to spread the caramel around the base. It doesn’t matter if it’s uneven, it will melt later.

In a saucepan, bring the milk up to body temperature. Whisk in the eggs and the 90g of sugar until well mixed. Pour into the dish.

Place the dish in a bain marie – basically a much larger oven proof dish with boiling water coming halfway up the side of the flan. Bake for 45 minutes to an hour. If it starts to brown too much, cover it with foil.

When you remove the flan from the oven, it will still be a bit jiggly – it will cool as it sets. When it is almost completely cool, run a knife around its edge, put a plate on top and turn it upside down. Serves 6.

Do you have a dessert you’ve never been game to prepare?

Aren’t other peoples’ families zany? It always seems that way to me. When I was a kid, other peoples’ houses were just different; they looked different, smelled different, ran differently. To a six-year-old child, the familiar, their home, has no smell, no particular look, no discernible system of organisation. It just is. Our own environments are the very definitions of normality. To us…

It isn’t until we find ourselves in someone else’s environment that we are forced to realise that our way of doing things is just one way, not the way. It’s easy to criticise the unfamiliar, from the way someone washes the dishes to the way they run their household. And when you move in with people you weren’t brought up with, their ways will almost certainly be at odds with yours, something which you may not have even considered before.

How is all this relevant? Mousse Chocolate (moos cho-ko-let, not moos chok-let), which is what my boyfriend and his family will call this recipe for all eternity, is technically a mistranslation. The name in Portuguese is literally ‘Mousse of Chocolate’. The name has always sounded slightly wrong to me.

But ‘Chocolate Mousse’ would sound wrong to my boyfriend’s ears. In addition, ‘Chocolate Mousse’ to his family is something altogether different from what they prepare, something unbelievably creamy which, to a family that abhors cream, makes it unfitting for their beloved concoction of chocolate, eggs and sugar.

This was my second try at this recipe. The first time I made it I just couldn’t get the chocolate and egg whites to come together while still maintaining the mousse’s light and fluffy texture. I had a theory that without the pure fat of cream I’ve used in every chocolate mousse I’ve ever made, they just weren’t coming together, and that as such microwaved chocolate was more unforgiving. Then I noticed that many recipes call for a small amount of butter. So I bit the bullet and did the double boiler thing, butter and all.

So how was it? Rich? Yes. Creamy? No way. Delicious? Definitely. Mousse Chocolate.

Mousse Chocolate for two

2 eggs, separated

60-80g dark chocolate broken into pieces (I used nestle club but next time I think I’ll use something with a bit more depth of flavour).

1 Tablespoon of butter

2 teaspoons of sugar (optional- I left it out but in hindsight I think it needed it)

Beat the egg whites to stiff peaks in a completely clean and dry bowl. Set aside.

Put chocolate in a bowl over a pan of simmering water. Make sure the water is not touching the bowl, the bowl should just be ‘steamed’.

When the chocolate begins to melt, add the butter and sugar if desired. Once melted together, turn off the heat. Stir in egg yolks one at a time, very quickly.

Remove the bowl from the pan and fold in a third of the beaten egg whites. Fold in another third gently and then the remaining third even more gently.

Put mix in container/s, cover with cling film and set for at least four hours.

Don’t tell my boyfriend, ‘cause he’ll just say ‘I told you so’- I didn’t really like custard until we went to Portugal. When it came to dessert, I was strictly a chocolate-something-served-with-lashings-of-whipped-cream kind of gal. I didn’t really understand the fascination with that sweet, thick, eggy goo. That was until I’d been to Belém and tried the famous tarts that have been made their since 1857. Fresh from the oven, rich, golden and irresistibly crunchy and sprinkled liberally with cinnamon. I still have dreams about them. Sigh.

No, I’m not going to give you a recipe for pasteis de nata (or as they’re known here, Portuguese custard tarts) for the simple reason that there is no way in hell I would ever attempt to make such a thing. For anyone who knows anything about pastry making, making pasties de nata is akin to making custard from scratch on top of making croissants. I ate one every day for breakfast (and many other meals) when I was in Portugal a few years ago, and I can tell you that no Portuguese person would ever make them either – not when you can buy them on practically every street corner for 60 euro cents each.

But what I do like to make, especially to use up any old egg yolks, is homemade custard. Now this may sound fiddly or possibly disastrous but let me assure you as someone with zero patience, it’s not. If the custard gets a bit lumpy, you can always strain it through a sieve, no big deal. And what’s more, it’s made with ingredients most people have on hand. It can be eaten warm or cold, sprinkled with cinnamon and sugar and baked or used as a filling for or accompaniment to various desserts. And what makes it Portuguese? Probably just the sheer number of egg yolks used…

Rich Portuguese Custard (from ‘The Taste of Portugal’ by Edite Vieira)

600ml full cream milk

4-6 egg yolks (I used 4)

1 Tablespoon plain flour

140g caster suger

1 strip lemon peel or a vanilla pod

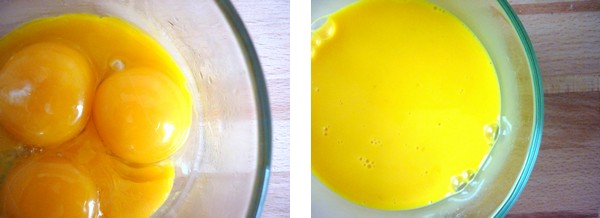

Mix 3 Tablespoons of milk with the flour and another 3 Tablespoons of the milk with the egg yolks. Set each mixture aside. Score the vanilla pod down the centre if using to allow the seeds to escape while cooking the custard.

Warm the remainder of the milk with the sugar and lemon peel or vanilla pod on a low heat. Mix in the flour paste carefully with a wooden spoon and then slowly bring to the boil, stirring constantly. Cook about 4 minutes.

Remove from the heat and sit for a few minutes. Gradually add the egg yolk mixture in a thin stream, whisking constantly. Still whisking, place back on the heat and cook for one minute.

Remove the vanilla pod or lemon peel and serve.

So, dear readers, do you prefer to eat your custard hot, cold, or not at all?

About me

Sharing easy recipes, hunting down the best coffee. Honest accounts, nothing too serious. Read more...

Sharing easy recipes, hunting down the best coffee. Honest accounts, nothing too serious. Read more...Recent Posts

- Aerpress means no more shit #travelcoffee and #workcoffee

- Why I write and four ace bloggers who do it better

- The five best things I ate in London

- Shoreditch is awesome, airports are not

- I quit sugar? Do I bollocks.

- Cubao Street Food, Alexandria

- The Reformatory Caffeine Lab, Surry Hills

- Brewtown Newtown

- Stay caffeinated over Christmas

- Gumption by Coffee Alchemy, Sydney CBD

Popular posts this month…

Sparkling Long Black posted on May 10, 2011

Sparkling Long Black posted on May 10, 2011  Review – Philips Saeco Intelia posted on January 10, 2012

Review – Philips Saeco Intelia posted on January 10, 2012  Kosher Whole Orange Cake posted on July 5, 2011

Kosher Whole Orange Cake posted on July 5, 2011  Cheat’s Dulce de Leche posted on January 7, 2011

Cheat’s Dulce de Leche posted on January 7, 2011  The quest for Mex part 2 – Feisty Chicken Burritos posted on December 21, 2010

The quest for Mex part 2 – Feisty Chicken Burritos posted on December 21, 2010  Salat Hatzilim posted on January 28, 2011

Salat Hatzilim posted on January 28, 2011  Sri Lankan Spinach with Coconut posted on December 10, 2010

Sri Lankan Spinach with Coconut posted on December 10, 2010  Lau’s Ultimate Corn Fritters and the four fritter truths posted on March 1, 2013

Lau’s Ultimate Corn Fritters and the four fritter truths posted on March 1, 2013

Disclaimer:

All opinions in this blog are mine, an everyday, real-life person. I do not accept payment for reviews and nor do I write sponsored posts. I do not endorse the content of the comments herein.